Most people’s diaries are probably pretty boring to everyone else. (I’m pretty sure mine would be.) But not this one! During an incredibly difficult and stressful two years, Anne Frank chronicles her life cooped up with a bunch of other fugitives, hiding from the Nazis above an Amsterdam office. The diary entries are open and intimate, addressed to a fictitious friend “Kitty”. She writes mostly about herself and her interactions with her family and the others she spends time with. Her views on her family, especially her parents, seem fairly typical for a teenager, but she deals with the frustrations amazingly well given the pressure-cooker situation they are all in.

Continue reading

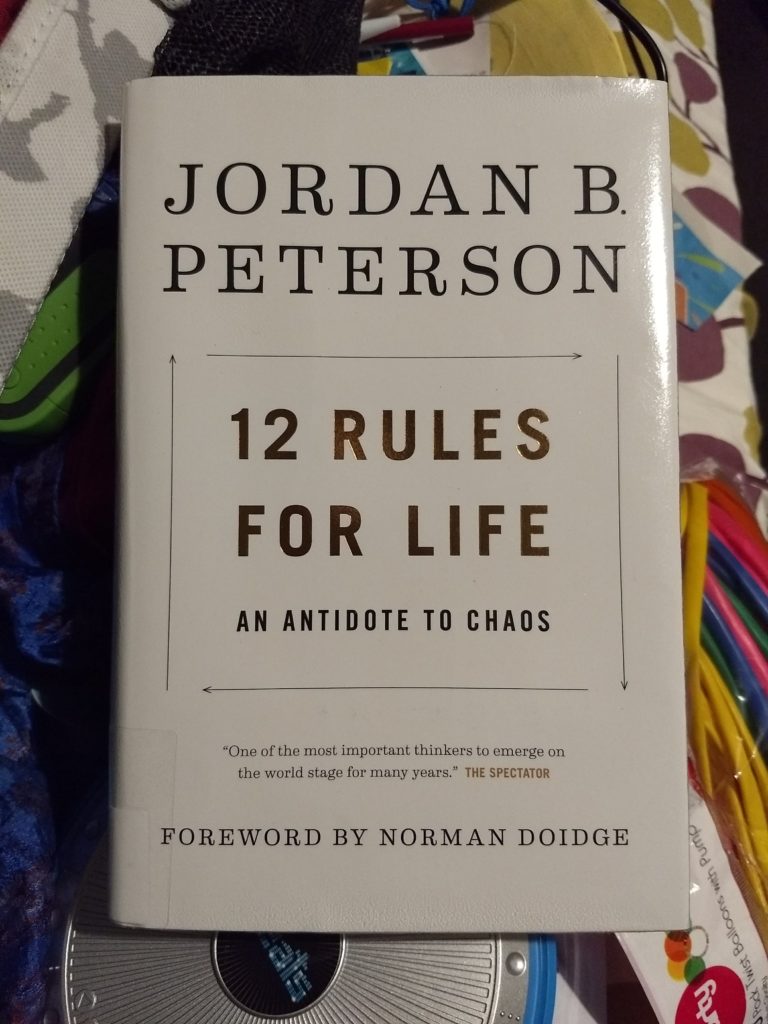

This is fun to read and it may change your life. The subtitle describes it best: chaos (particularly perhaps the chaos of the modern world) is what Peterson dreads, and he offers prescriptions, strategies and even commandments for how to preserve an ordered and civilised life from the relentlessly pounding waves of entropy. And all presented using language that virtually demands to be read out loud.

This is fun to read and it may change your life. The subtitle describes it best: chaos (particularly perhaps the chaos of the modern world) is what Peterson dreads, and he offers prescriptions, strategies and even commandments for how to preserve an ordered and civilised life from the relentlessly pounding waves of entropy. And all presented using language that virtually demands to be read out loud.