The first half of the book is dizzying — stupid — hilarious — it’s a series of seemingly random impressions, vignettes, observations and ideas of a narrator who is an Internet celebrity and is steeped in Internet culture.

Continue reading

The first half of the book is dizzying — stupid — hilarious — it’s a series of seemingly random impressions, vignettes, observations and ideas of a narrator who is an Internet celebrity and is steeped in Internet culture.

Continue reading

This is the fictional autobiography of one Humbert Humbert, written in his jail cell near the end of his life. He is very erudite and quite engaging despite being unhealthily obsessed with young girls. He falls in love with the title character (his landlady’s young daughter) and ends up taking her on an extended road trip across the USA. They purport to be father and daughter but are actually lovers. At the beginning Lolita seems reasonably willing to go along with everything, but Humbert gradually reveals how controlling he is and how unhappy Lolita really is. He slowly loses his grip and eventually loses Lolita, and commits the crime that finally lands him in jail. The writing throughout is clever, inventive and endlessly rewarding to read, despite the bleak and tawdry subject matter.

Continue reading

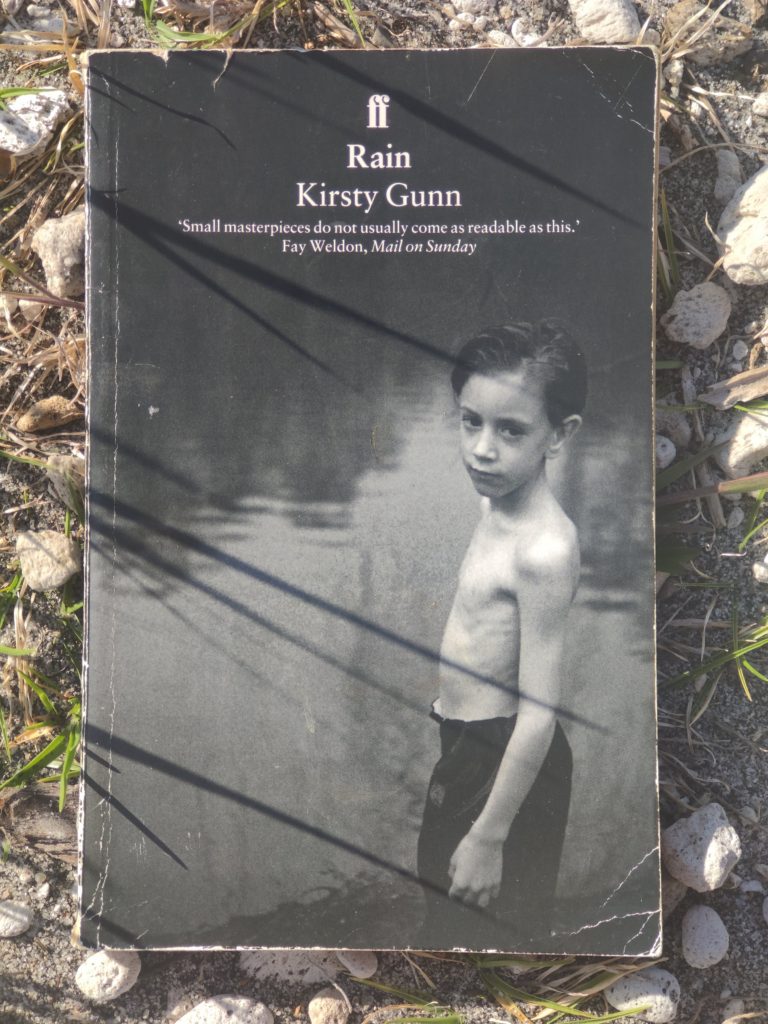

Did you ever read a book or watch a film where you could just tell that something awful was going to happen? You dreaded the turn of every page in anticipation of the imminent horror. And yet you just had to keep reading, to find out what actually happens.

Continue reading

I do love a good time-travel story. A middle-aged man has a heart attack and dies – and then wakes up again as a young man back in his college days. Once he figures out what has happened, he sets about figuring out how to deal with it. He’s got an amazing opportunity to replay his life, fixing all the mistakes and maybe becoming rich too. (If it happened to me I would definitely be buying quite a lot of Bitcoin.)

Continue reading

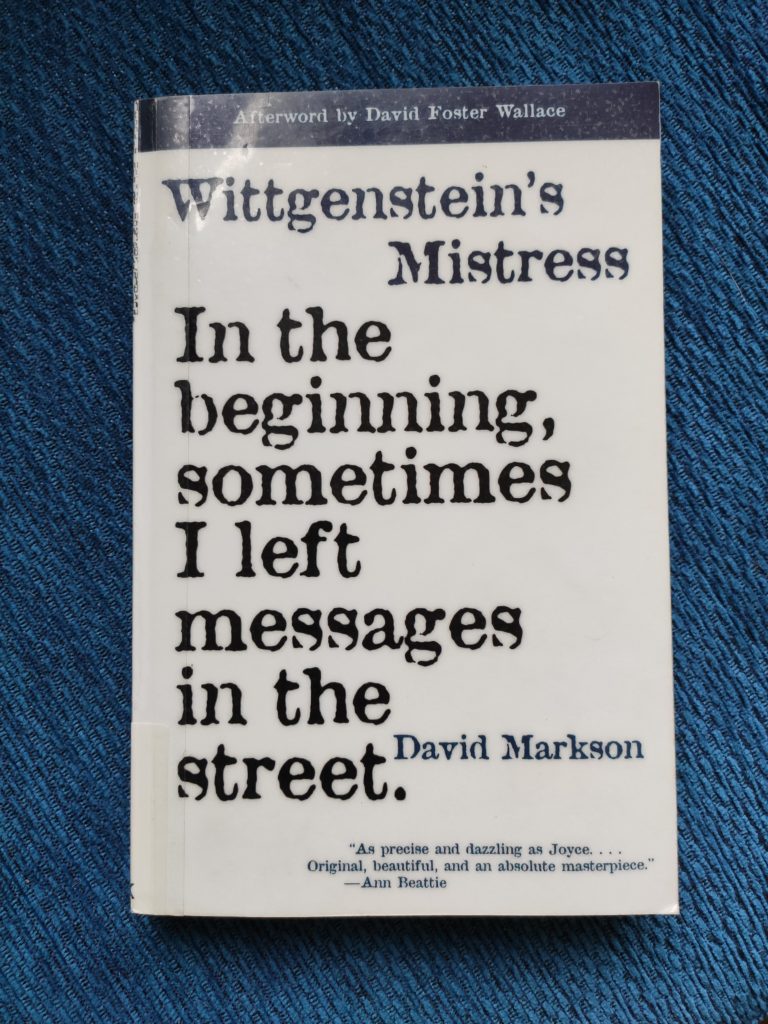

This book is a diary written by the last person on earth. It’s not initially clear what happened to everyone else, but we find out that she has been alone for some years, travelling around in abandoned cars and living in various interesting abandoned buildings (such as museums). It becomes clear that she is becoming a bit unhinged; understandable in her circumstances. To me this book reads like a study in memory, regret and self-deception, though that makes it sound a bit grim; there is a fair bit of humour in this book. The overall tone is reminiscent of Markson’s This is Not a Novel. Wittgenstein’s Mistress is more conventional, but that wouldn’t be hard: it’s still a strange, amusing and unsettling read.

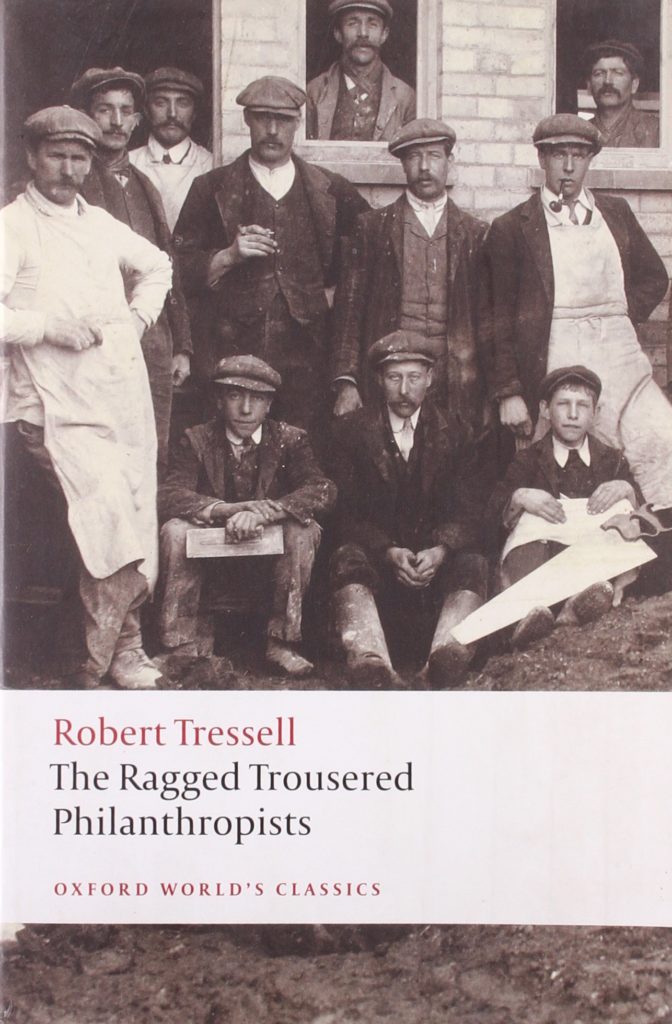

A hundred or so years ago, the English working classes had terribly rough lives.They spent half their time working under harsh conditions and the other half desperately looking for work. They never had enough food or clothing. But despite their ragged clothing they were content to spend their lives working for the betterment of their fellow men — in particular, their employers, who did no productive work themselves but instead spent their time cheating and exploiting their clients and employees.

Continue reading

This affecting story has a bit of mystery and a satisfying resolution, and some lovely writing along the way. I also quite appreciated the single-word chapter titles, which reinforce an atmosphere of uncertainty throughout.

Continue reading

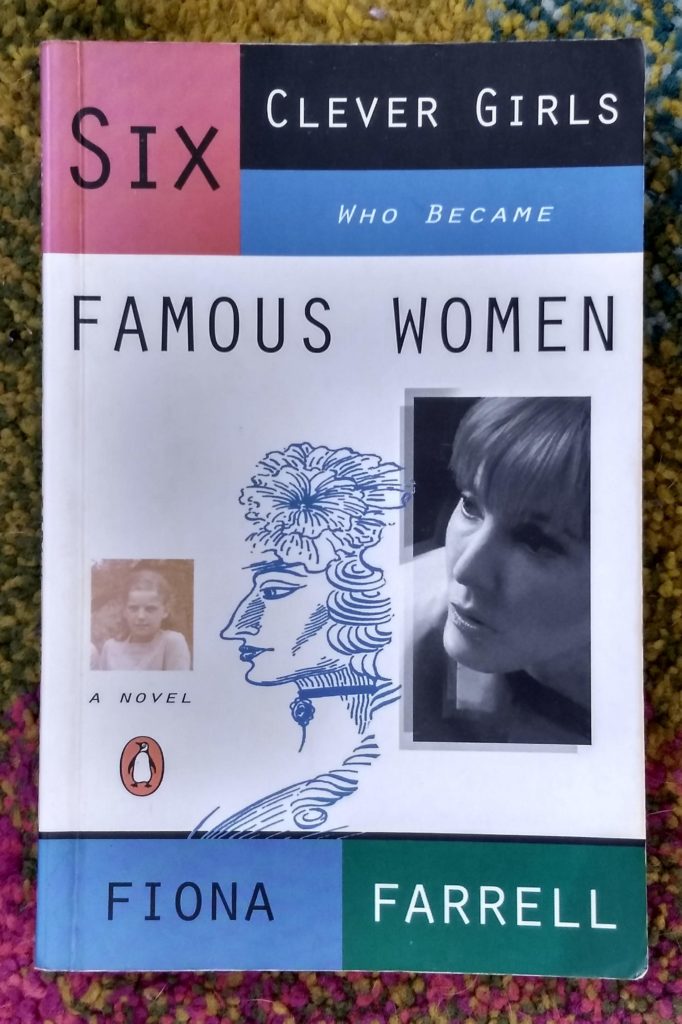

This book starts out as a day in the life of a group of six schoolgirls. This is a world that is unfamiliar to me, so it seemed exotic and yet still quite believable. After establishing the characters and putting them through some ups and downs, we fast-forward several years: we get to see the girls as adults, see how they’ve changed but how they mostly haven’t, and see how they deal with the directions their lives have taken. It’s a nice ensemble piece. The women are more or less relatable but they are all interesting, and their stories are full of nicely-rendered moments. And there are some very satisfying resolutions too.

Many people consider this to be the greatest novel ever written, and who am I to argue — I loved it. The main characters are well-rounded and believable — I especially liked the man-about-town Oblonsky (he of the famous unhappy family which is unhappy in its own way) and the solid and thoughtful Levin (Tolstoy under another name).

Continue reading

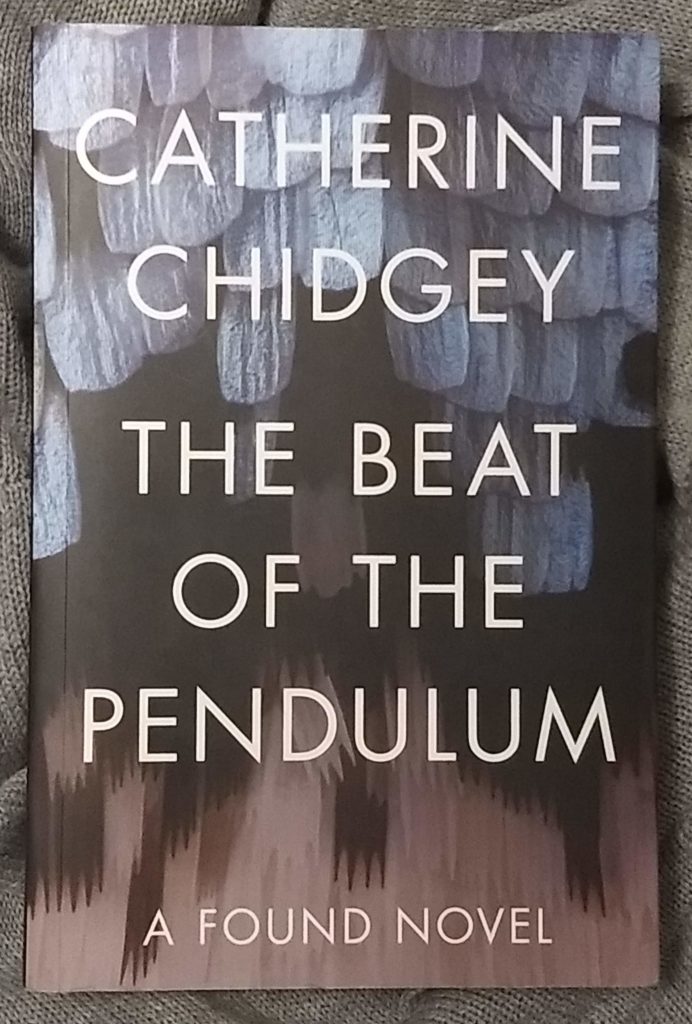

This experimental “found novel” is great. Once I got into it, it was like a beautifully edited minimalistic fly-on-the-wall documentary in print.

Every day for a year, Catherine Chidgey recorded or wrote down a conversation, email, overheard snippet, advertisement or some other piece of text. That’s what this book is. Initially it’s pretty disorienting as there’s only speech — no introductions, descriptions or even “he said” or “she said”. It takes a while to figure out who the characters are and what their relationships are. Even by the end of the book I was still losing track of who was talking during long conversations.

Continue reading