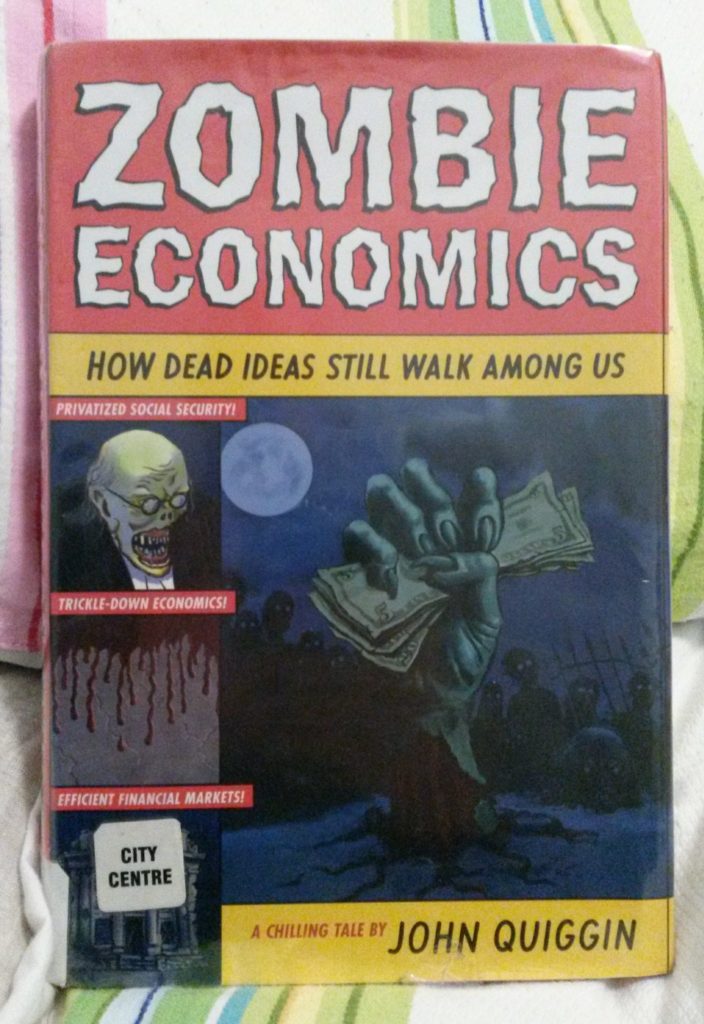

A taste for paradoxical reasoning is common among economists, to the point where it is a job requirement in some circles.

— Zombie Economics, p112

That’s a good summary of this book. It argues that a lot of the foundations of current economic thinking are outdated, and have in some cases been entirely disproved, and yet they still influence policies to everyone’s detriment.

Trickle-down economics has now been thoroughly discredited. An IMF discussion paper says, “The poor and the middle class matter the most for growth via a number of interrelated economic, social, and political channels.” It’s easier and easier to find similar views, even from authorities like the World Bank. Yet we still hear people saying that tax cuts for the rich will benefit the rest of us.

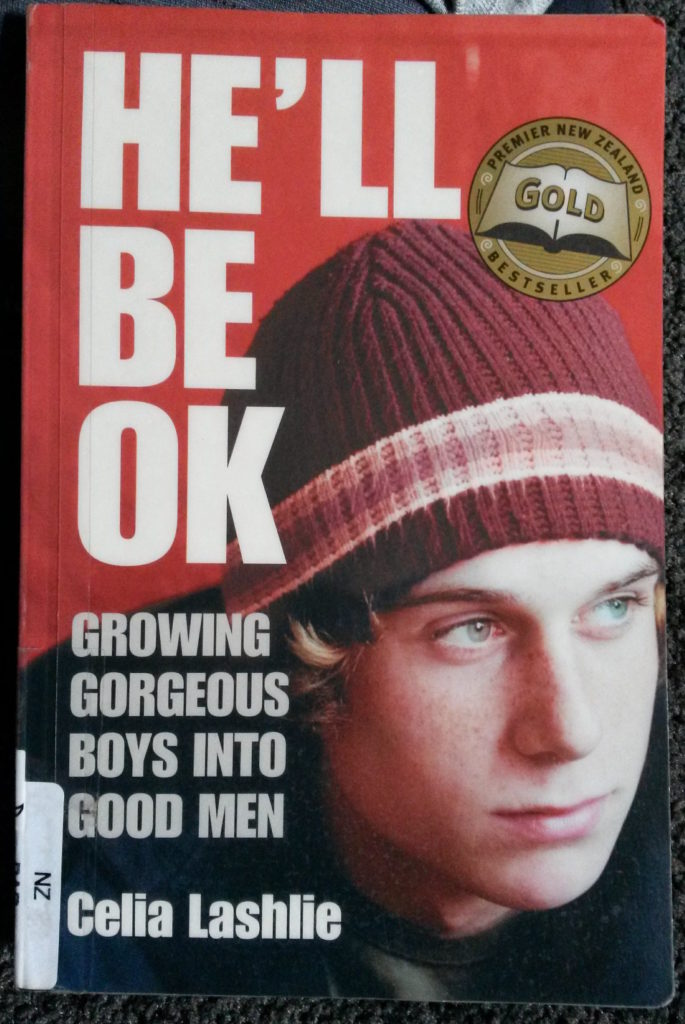

This book is about raising boys, especially teenagers. It’s heartfelt and compelling, and it has a lot of good things to think about and remember if you have a teenaged son, or are planning to have one.

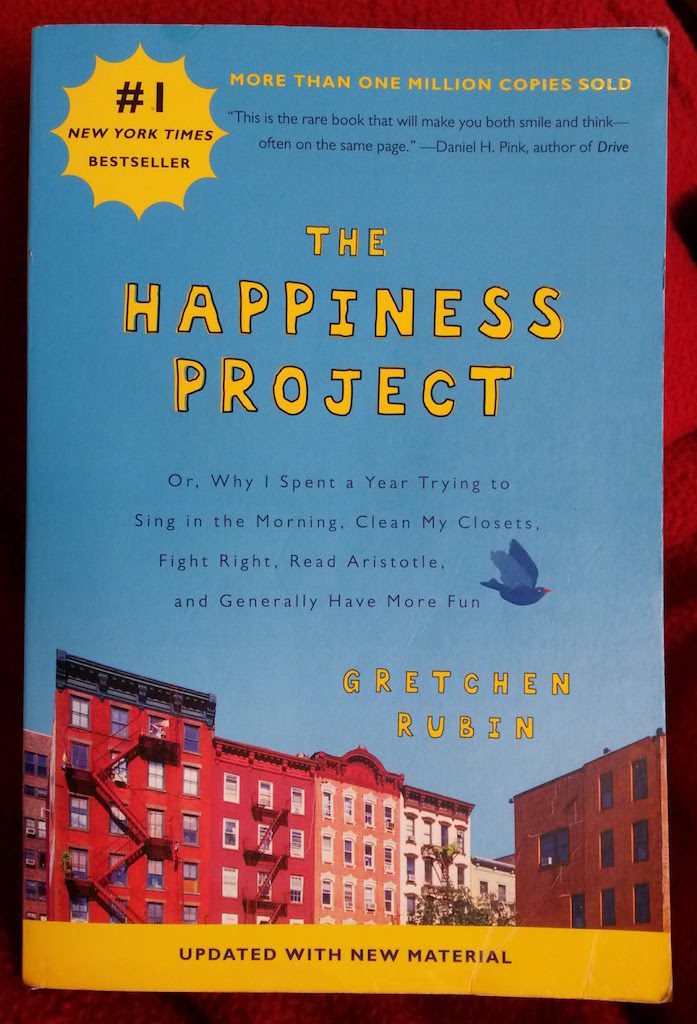

This book is about raising boys, especially teenagers. It’s heartfelt and compelling, and it has a lot of good things to think about and remember if you have a teenaged son, or are planning to have one. This book made me happy. Gretchen Rubin did her research, found out every possible method for becoming more happy, and then spent a year trying them all out. In the end she decides it has worked — she is happier — and she evaluates which methods worked best for her. She’s read a stack of popular psychology books and self-help guides, so we won’t have to.

This book made me happy. Gretchen Rubin did her research, found out every possible method for becoming more happy, and then spent a year trying them all out. In the end she decides it has worked — she is happier — and she evaluates which methods worked best for her. She’s read a stack of popular psychology books and self-help guides, so we won’t have to.

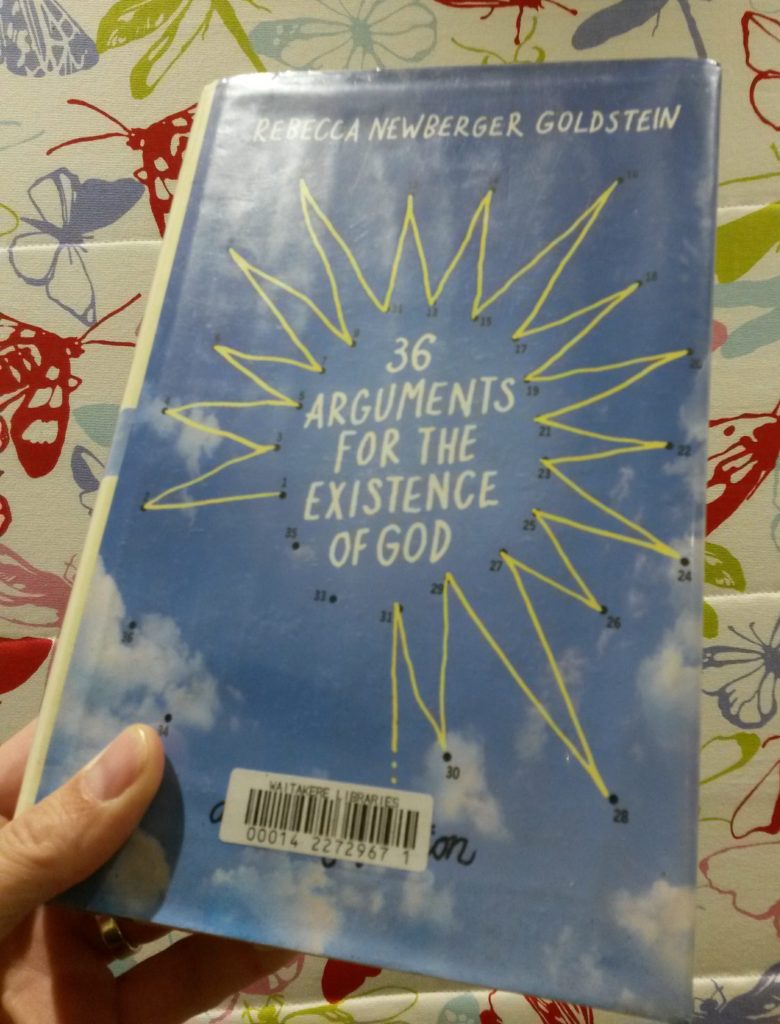

This is a fascinating book about poetry, disguised as a wry and humorous story about a poet with writers’ block. It’s like two books in one!

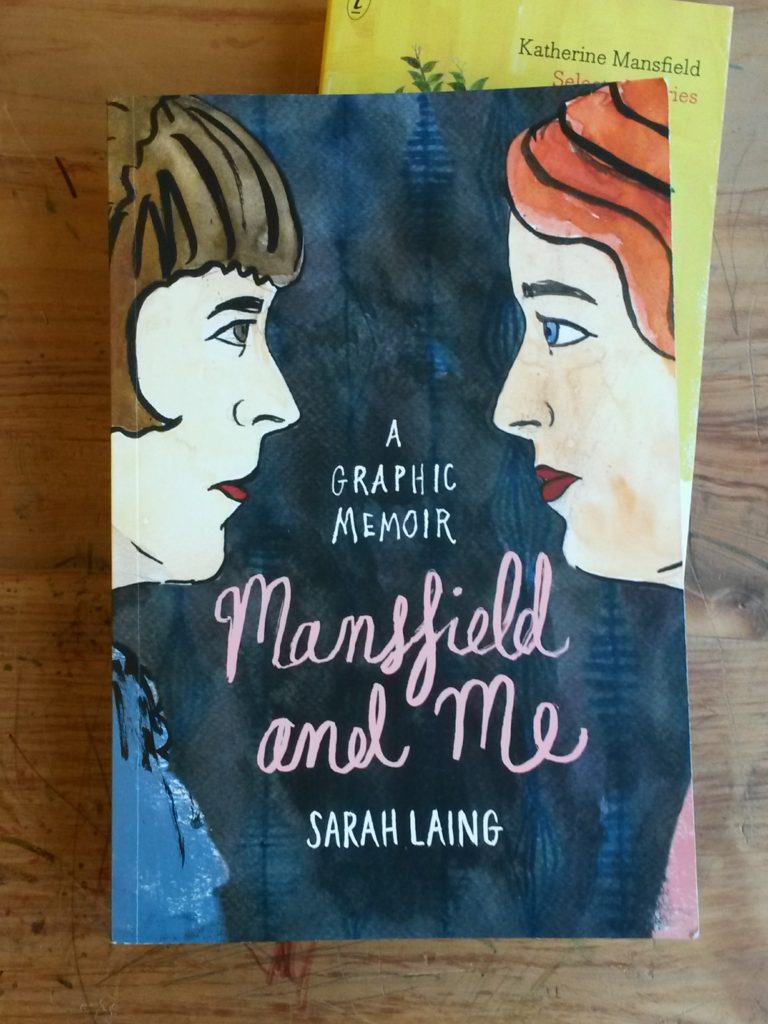

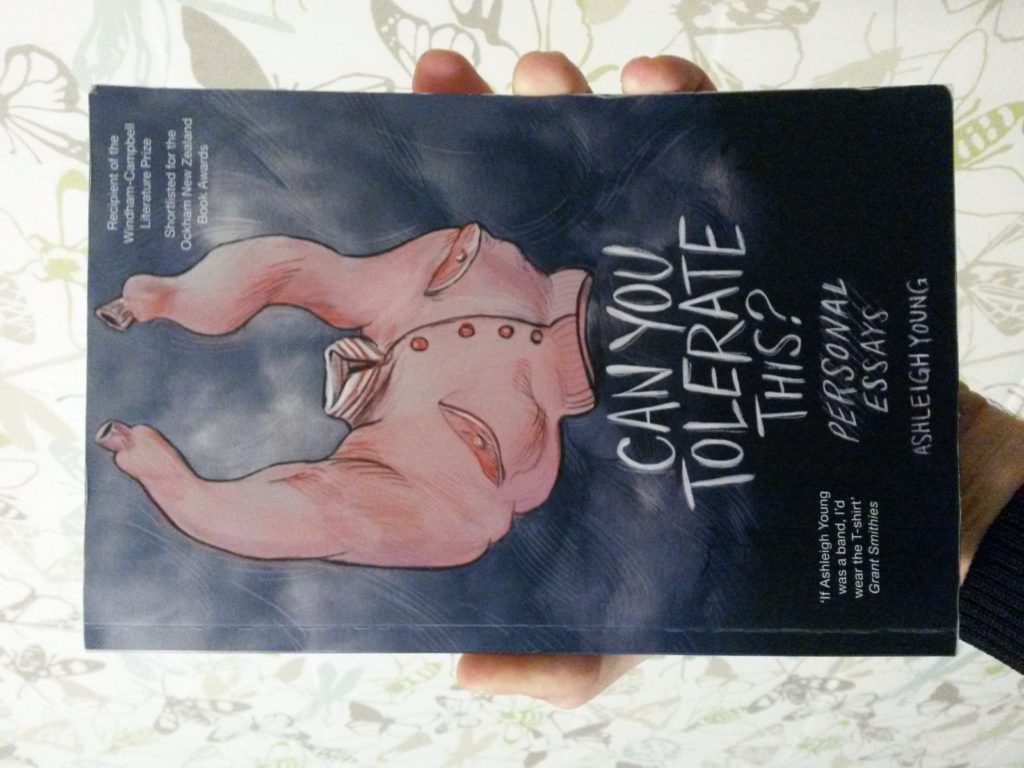

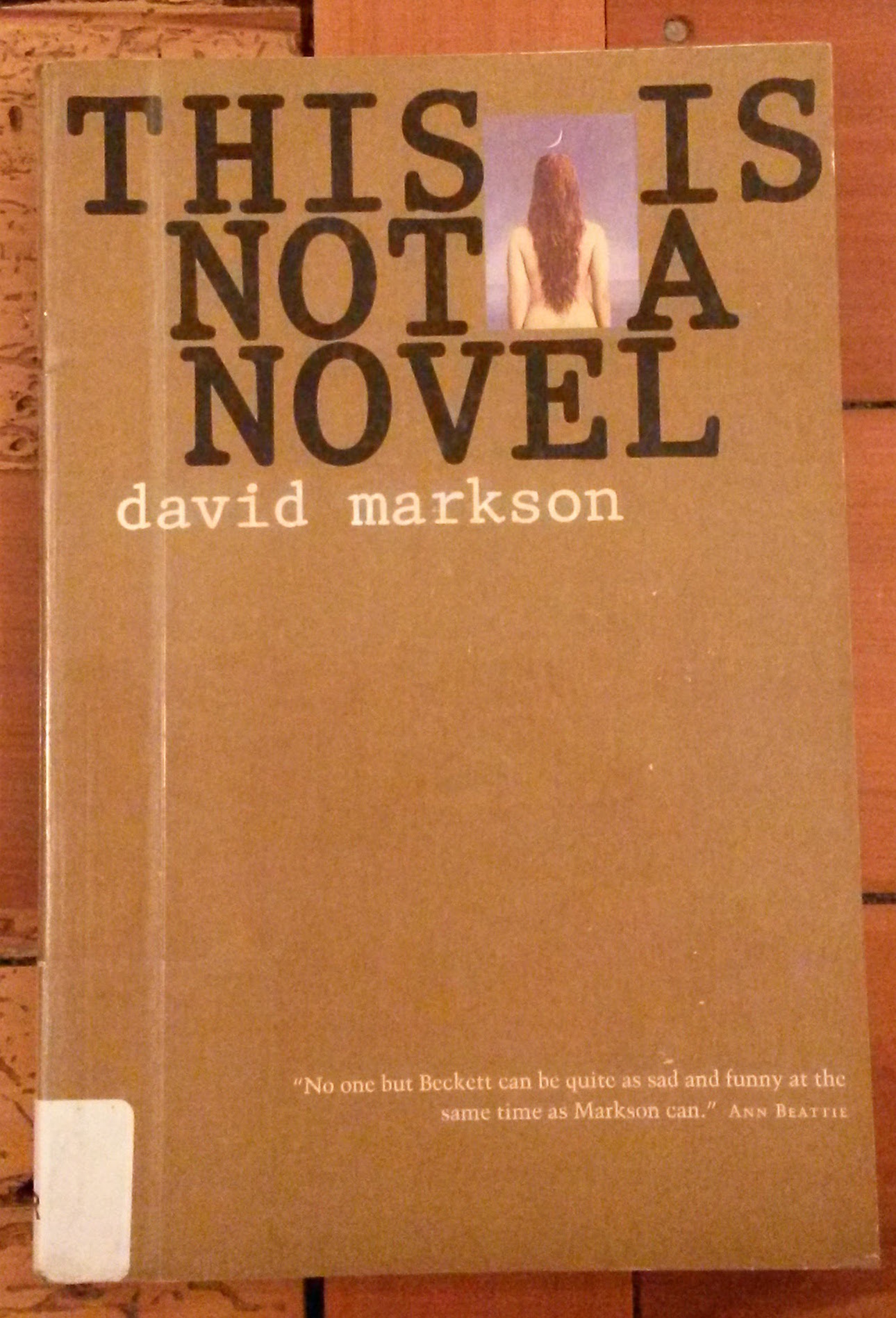

This is a fascinating book about poetry, disguised as a wry and humorous story about a poet with writers’ block. It’s like two books in one! I have never read a novel like this before, but that’s obvious since it is actually not a novel. (The clue is in the name.) But it has characters (well, a character), lots of historical figures, and a (very faint) narrative arc. And it’s pretty fun to read.

I have never read a novel like this before, but that’s obvious since it is actually not a novel. (The clue is in the name.) But it has characters (well, a character), lots of historical figures, and a (very faint) narrative arc. And it’s pretty fun to read.