This story is about a tomboyish girl called Stephen. It traces her life from her birth and upbringing in a wealthy and genteel English family in the late 1800s, through the first world war and on to a successful career. She never feels quite comfortable conforming to the model of a well-brought-up young woman, and it takes many years to realise what the reader already knows, that she is (in her own words) an “invert”. Of course, such things were not discussed back then, at a time when the authorities did not even acknowledge lesbianism’s existence, and would have made it illegal if they had. The book was banned (and burned) on publication in 1928 in England.

This story is about a tomboyish girl called Stephen. It traces her life from her birth and upbringing in a wealthy and genteel English family in the late 1800s, through the first world war and on to a successful career. She never feels quite comfortable conforming to the model of a well-brought-up young woman, and it takes many years to realise what the reader already knows, that she is (in her own words) an “invert”. Of course, such things were not discussed back then, at a time when the authorities did not even acknowledge lesbianism’s existence, and would have made it illegal if they had. The book was banned (and burned) on publication in 1928 in England.

Initially I couldn’t warm to Stephen because she is so privileged in many ways. She’s rich, physically masterful, intelligent, and has a very supportive and understanding father and other carers. She’s also a brilliant equestrian, fencer and writer. But I realised that this just throws her problems into stark relief — nobody will explain or even acknowledge her feelings of not belonging; hence she does spend a lot of time in the “well of loneliness” of the title. She rails against the unfair fact that she will never be able to acknowledge her partner as such, or even to grieve her properly if she dies, without suffering awful societal consequences. It reminded me of the film Four Weddings and a Funeral, where (spoiler alert) even at Gareth’s funeral, Matthew, his loving partner of many years, could be referred to only as “his closest friend”.

Continue reading →

What would life be like if we communicated with music instead of words? That’s the situation in the dystopian future of The Chimes. People have lost most of their ability to remember in words, so they must rely on objects to prompt their memories, and an intricate musical language to communicate. Simon, a young man, fetches up in London with only a vague idea why he came and what he’s supposed to do there. Things start happening to him, and before long he starts making things happen himself. Eventually he becomes part of a revolutionary struggle.

What would life be like if we communicated with music instead of words? That’s the situation in the dystopian future of The Chimes. People have lost most of their ability to remember in words, so they must rely on objects to prompt their memories, and an intricate musical language to communicate. Simon, a young man, fetches up in London with only a vague idea why he came and what he’s supposed to do there. Things start happening to him, and before long he starts making things happen himself. Eventually he becomes part of a revolutionary struggle. This novel is Dorothy Forrest’s life story, and her complicated family life too. After reading it I felt that I knew her quite well…

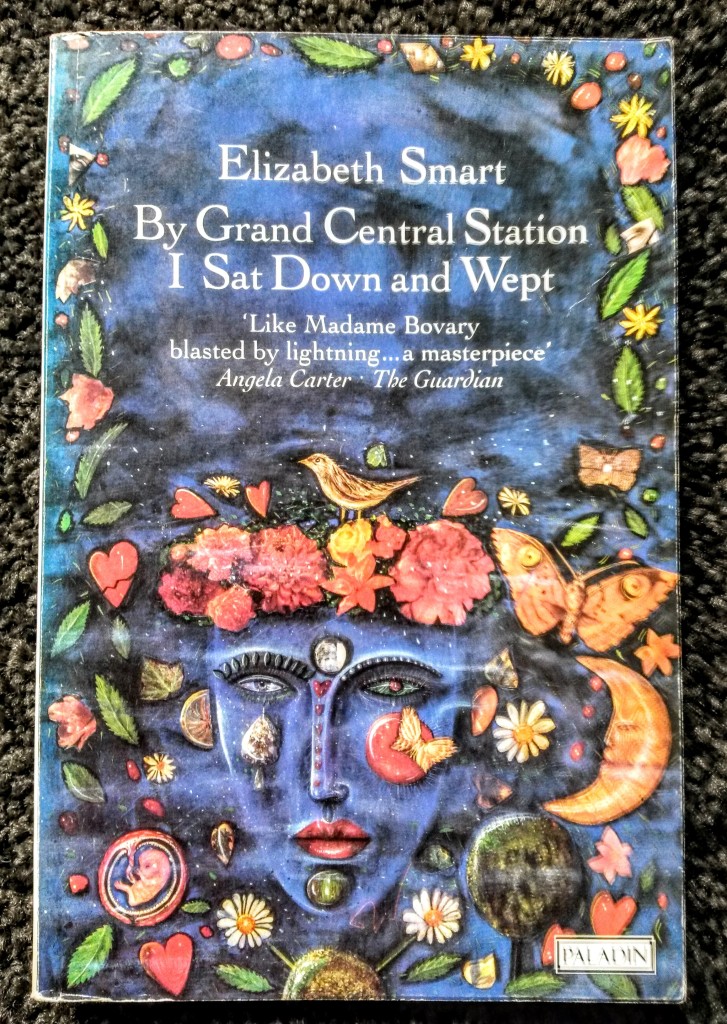

This novel is Dorothy Forrest’s life story, and her complicated family life too. After reading it I felt that I knew her quite well… This is an amazing prose poem spanning the author’s love affair with an older married man. The language is raw and rich and really takes you to another place, and usually not a happy one — when she isn’t miserable, she’s obsessively ecstatic. But wow, what a ride:

This is an amazing prose poem spanning the author’s love affair with an older married man. The language is raw and rich and really takes you to another place, and usually not a happy one — when she isn’t miserable, she’s obsessively ecstatic. But wow, what a ride:

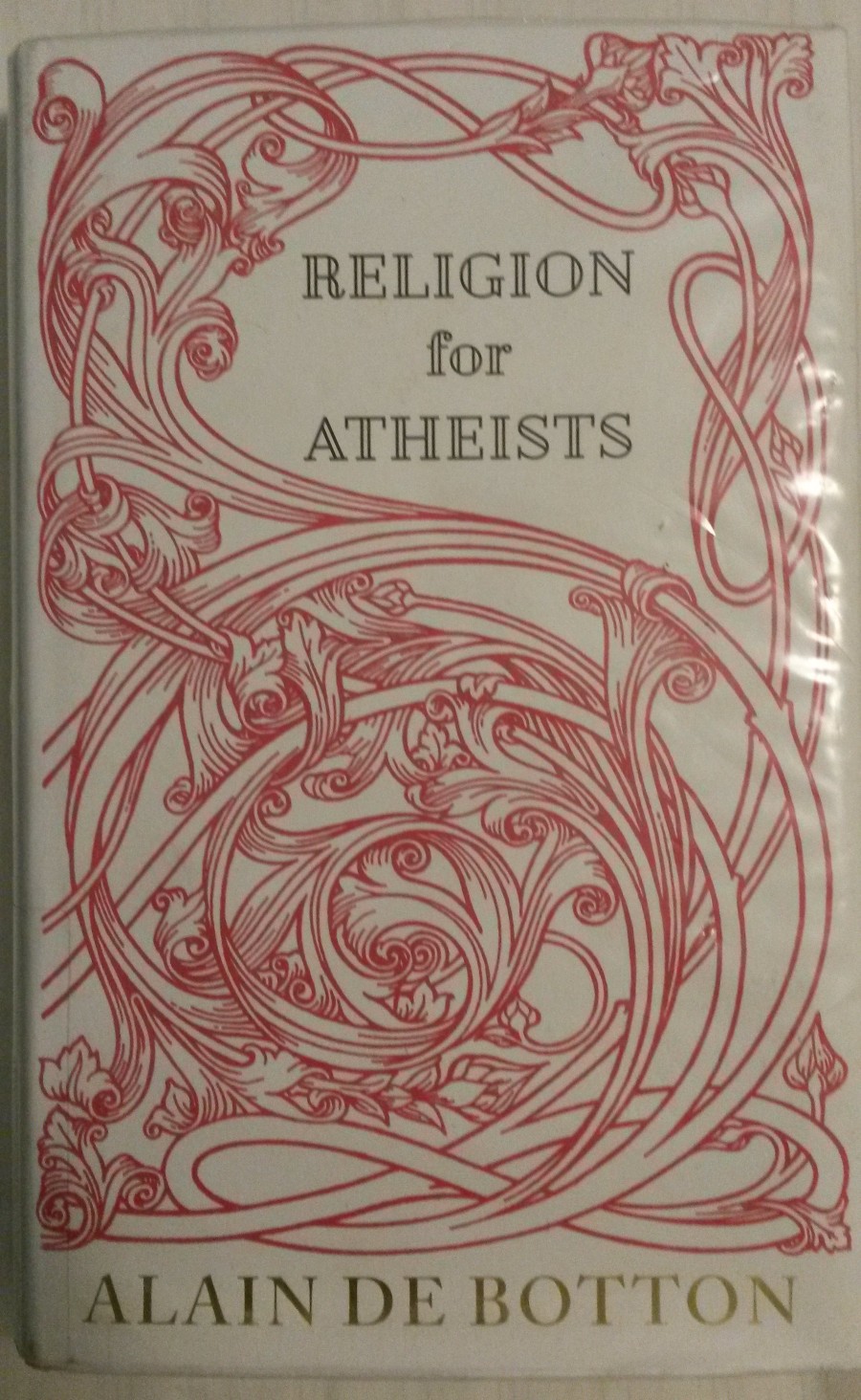

Most religions make metaphysical claims that are hard to believe, if they make any sense at all. But even if you don’t believe that the world rests on an elephant standing on turtles, or that omnipotent beings scrutinise our every move, religious traditions have a lot of ideas worth keeping. Religions place great importance on things like community and ritual, acknowledging our needs and our foibles too. This is what de Botton points out in this book.

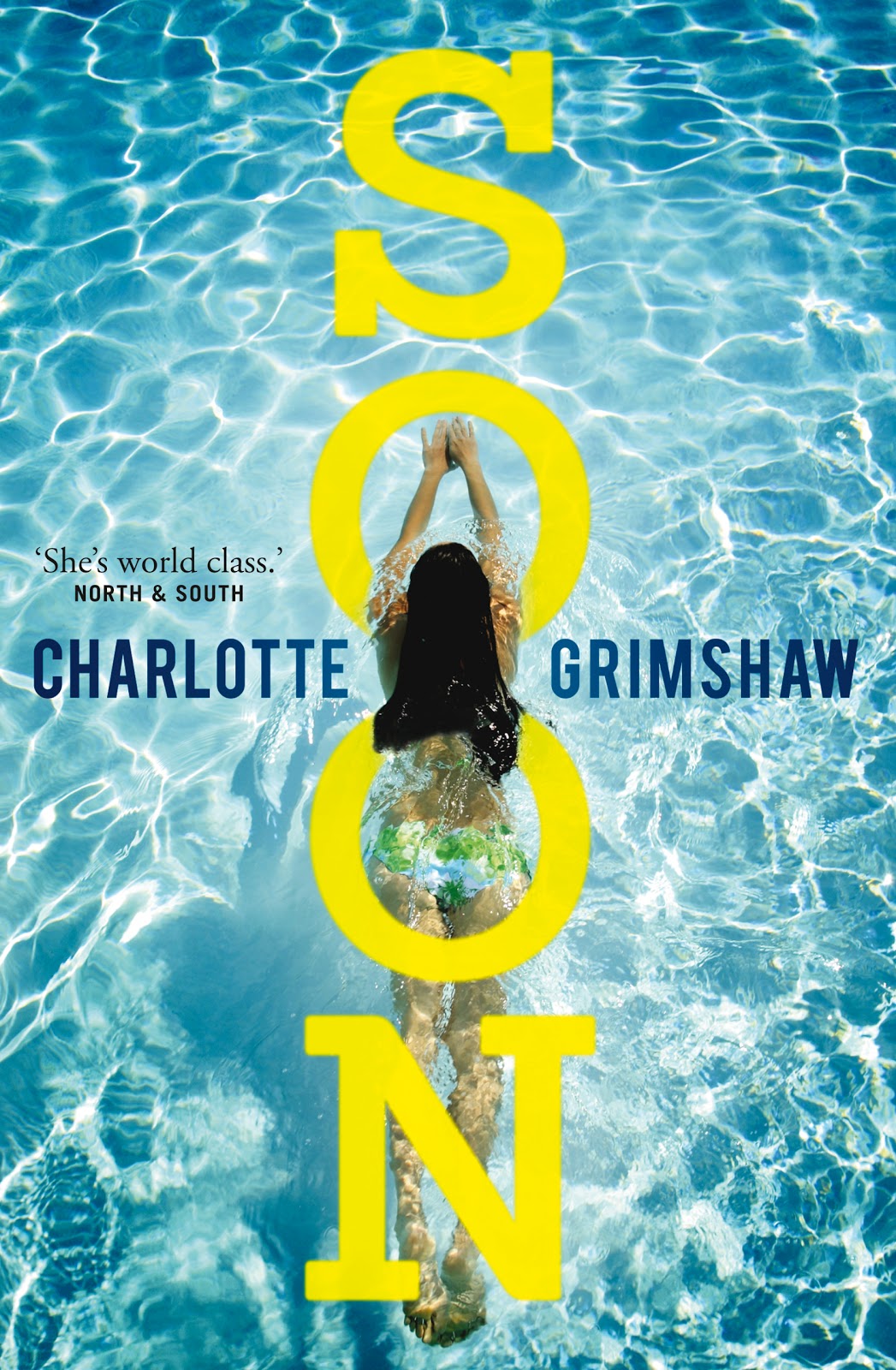

Most religions make metaphysical claims that are hard to believe, if they make any sense at all. But even if you don’t believe that the world rests on an elephant standing on turtles, or that omnipotent beings scrutinise our every move, religious traditions have a lot of ideas worth keeping. Religions place great importance on things like community and ritual, acknowledging our needs and our foibles too. This is what de Botton points out in this book. Two very interesting characters inhabit this story: Roza, the Prime Minister’s wife, a creative maverick who still manages to fit in with his circle; and her precocious young son Johnny, who is clever and manipulative and a bit of a nightmare. Throughout the novel, Roza tells Johnny a story featuring a large cast of characters including a nasty dwarf called Soon, and surreal happenings, all based on the other people in the novel. It’s like a terrifyingly twisted Enid Blyton romp, and it’s fun drawing parallels between Roza’s story and the novel.

Two very interesting characters inhabit this story: Roza, the Prime Minister’s wife, a creative maverick who still manages to fit in with his circle; and her precocious young son Johnny, who is clever and manipulative and a bit of a nightmare. Throughout the novel, Roza tells Johnny a story featuring a large cast of characters including a nasty dwarf called Soon, and surreal happenings, all based on the other people in the novel. It’s like a terrifyingly twisted Enid Blyton romp, and it’s fun drawing parallels between Roza’s story and the novel. The title describes the book: 23 things, some counterintuitive, some perhaps contentious, they you may not have realised about the economic system that the world runs on.

The title describes the book: 23 things, some counterintuitive, some perhaps contentious, they you may not have realised about the economic system that the world runs on. This story is about a tomboyish girl called Stephen. It traces her life from her birth and upbringing in a wealthy and genteel English family in the late 1800s, through the first world war and on to a successful career. She never feels quite comfortable conforming to the model of a well-brought-up young woman, and it takes many years to realise what the reader already knows, that she is (in her own words) an “invert”. Of course, such things were not discussed back then, at a time when the authorities did not even acknowledge lesbianism’s existence, and would have made it illegal if they had. The book was banned (and burned) on publication in 1928 in England.

This story is about a tomboyish girl called Stephen. It traces her life from her birth and upbringing in a wealthy and genteel English family in the late 1800s, through the first world war and on to a successful career. She never feels quite comfortable conforming to the model of a well-brought-up young woman, and it takes many years to realise what the reader already knows, that she is (in her own words) an “invert”. Of course, such things were not discussed back then, at a time when the authorities did not even acknowledge lesbianism’s existence, and would have made it illegal if they had. The book was banned (and burned) on publication in 1928 in England.