This short but thought-provoking book describes a way that New Zealand’s economy could be reorganised to focus on the wellbeing of all its citizens, defined as

This short but thought-provoking book describes a way that New Zealand’s economy could be reorganised to focus on the wellbeing of all its citizens, defined as

The ability to lead the kinds of lives that they value and have reason to value.

There’s a lot of NZ-specific information, but the ideas are universally applicable. The approach is a bit different from the ideas put forth by the usual suspects across the political spectrum. Paul Dalziel and Caroline Saunders believe a market economy is essential, but recognise that it must be managed to allow the markets to deliver their maximum benefit. Even the most free markets are still heavily regulated, most obviously by contract and property law, and this helps us see that regulation is not antithetical to free markets — it is essential.

As for the Big Government versus Small Government debate, Dalziel and Saunders argue that government should be big enough. Government’s job is to do the things that citizens cannot do individually or collectively, and to help them add value to the things they choose to do. But the onus is on citizens to initiate this process and to use this support for their own individual and communal wellbeing. This is a shift from the old welfare state to what Dalziel and Saunders call the wellbeing state.

Continue reading →

I love this book. It’s a heartfelt, clear-eyed, inspiring clarion call for everyone to get together to make the world more livable. Her ideas are all so practical and achievable that I actually feel hopeful that they could really happen.

I love this book. It’s a heartfelt, clear-eyed, inspiring clarion call for everyone to get together to make the world more livable. Her ideas are all so practical and achievable that I actually feel hopeful that they could really happen.

Notes purportedly written by a condemned man during the day before his scheduled execution. Hugo wrote this as a protest against the death penalty at a time when the guillotine was in enthusiastic use by the French authorities. It works well by humanising the doomed prisoner, though I feel it cheats a little by never detailing the crime that put him on death row in the first place. Still a powerful read.

Notes purportedly written by a condemned man during the day before his scheduled execution. Hugo wrote this as a protest against the death penalty at a time when the guillotine was in enthusiastic use by the French authorities. It works well by humanising the doomed prisoner, though I feel it cheats a little by never detailing the crime that put him on death row in the first place. Still a powerful read.

This short but thought-provoking book describes a way that New Zealand’s economy could be reorganised to focus on the wellbeing of all its citizens, defined as

This short but thought-provoking book describes a way that New Zealand’s economy could be reorganised to focus on the wellbeing of all its citizens, defined as A meditation on belonging, place, family and more. Kirsty Gunn did what Katherine Mansfield never did: she returned from the UK to live for a time in her home town of Wellington, New Zealand. She stayed in a cottage in Thorndon, the suburb where Mansfield grew up, on a scholarship to work on her “Katherine Mansfield project”. This book is the result.

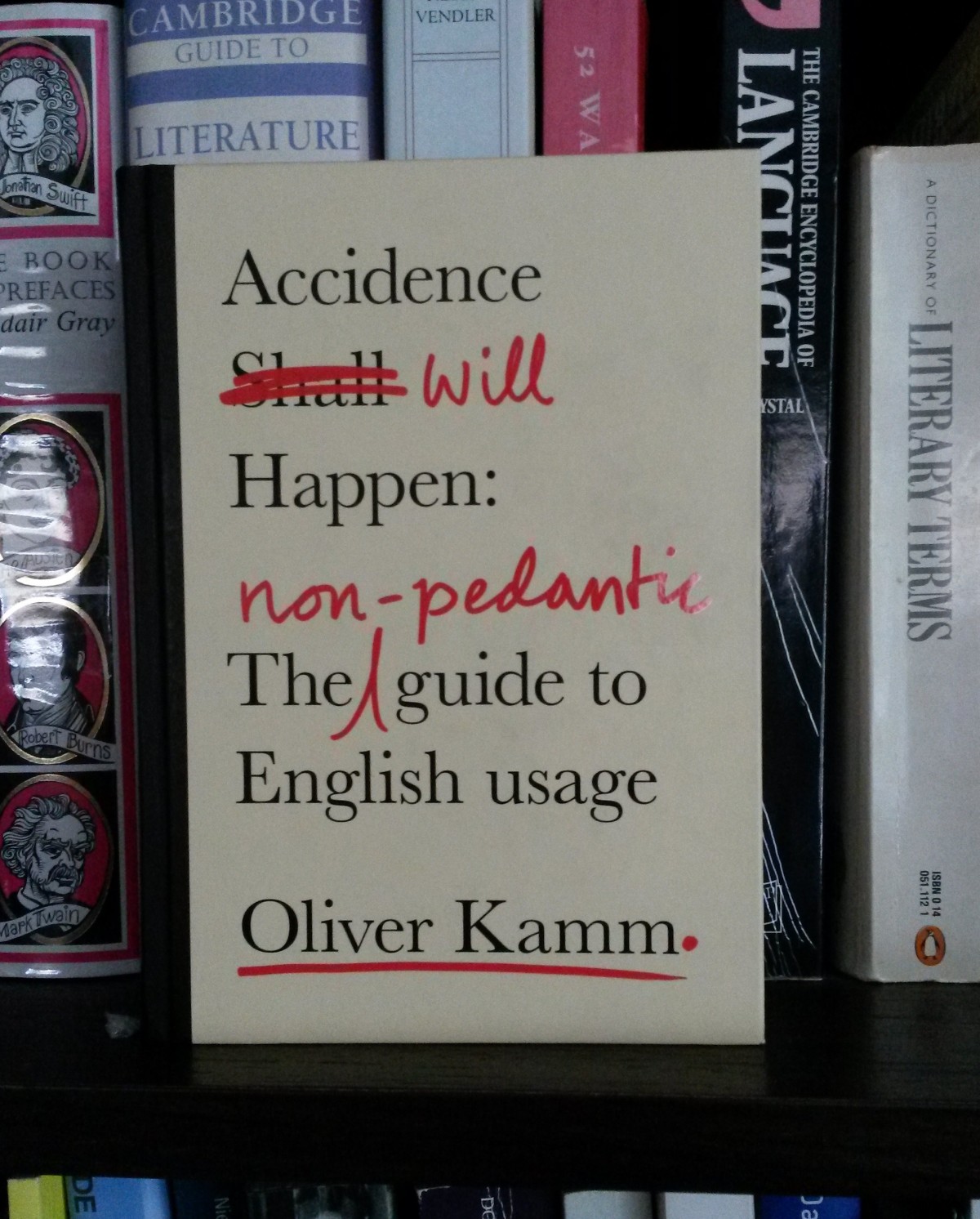

A meditation on belonging, place, family and more. Kirsty Gunn did what Katherine Mansfield never did: she returned from the UK to live for a time in her home town of Wellington, New Zealand. She stayed in a cottage in Thorndon, the suburb where Mansfield grew up, on a scholarship to work on her “Katherine Mansfield project”. This book is the result. In this book, Oliver Kamm attempts to explode a few myths about English usage, and set out sensible guidelines for literate writing. He gives interesting historical background notes and examples for many of his points, so the book is useful and well worth reading. But even though he chides “sticklers” for their insistence on idiosyncratic rules, his own rules and suggestions are themselves quirky and inconsistent. This makes the book a bit frustrating to read. It’s fun if you enjoy arguing with books though.

In this book, Oliver Kamm attempts to explode a few myths about English usage, and set out sensible guidelines for literate writing. He gives interesting historical background notes and examples for many of his points, so the book is useful and well worth reading. But even though he chides “sticklers” for their insistence on idiosyncratic rules, his own rules and suggestions are themselves quirky and inconsistent. This makes the book a bit frustrating to read. It’s fun if you enjoy arguing with books though.