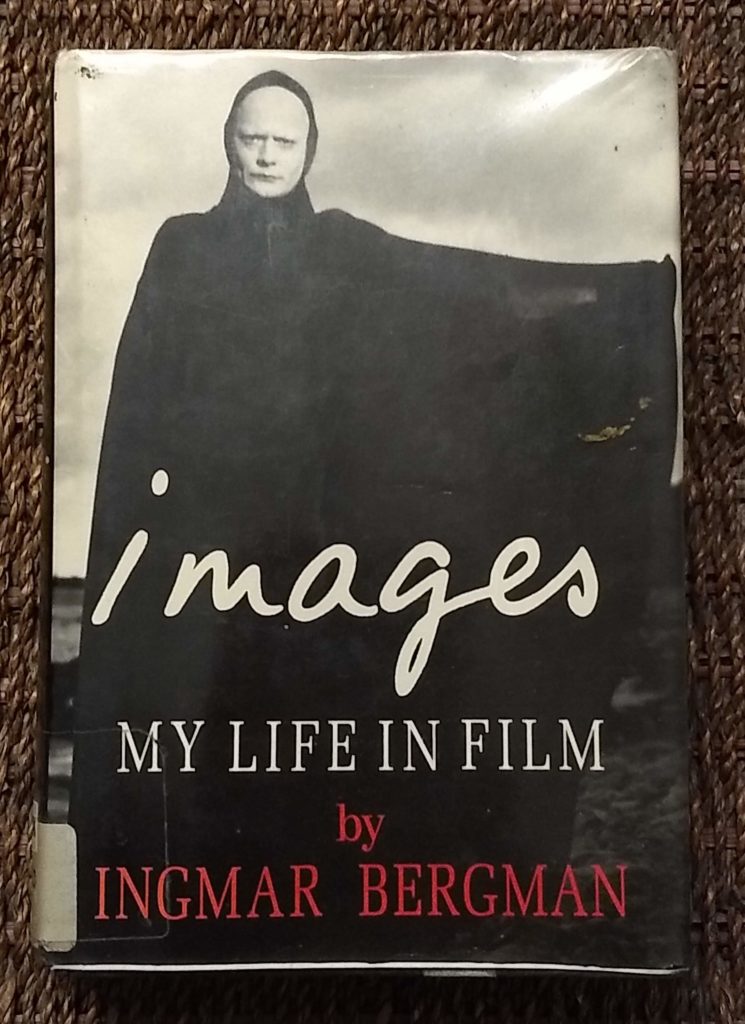

I have never seen an Ingmar Bergman film. They have always seemed to me to be the epitome of impenetrable, confusing European art-house cinema. This book doesn’t change that impression, but it does make me want to watch some of these films.

Continue reading