Snap judgements are surprisingly accurate. Even the ones we make without knowing how. Even the ones we make when we don’t even know we are doing it: “I just had a bad feeling about him, I can’t explain it”. This book gives evidence and explanations for this. It’s interesting in itself, but the trouble is it has been a very influential book — since it was published, its examples have been cited and reused so many times in so many places that what must once have been groundbreaking now seems overly familiar. I had similar thoughts the last time I saw a performance of Hamlet: the dialogue just seemed to be one cliche after another. Of course, they weren’t cliches when Shakespeare wrote the play!

Snap judgements are surprisingly accurate. Even the ones we make without knowing how. Even the ones we make when we don’t even know we are doing it: “I just had a bad feeling about him, I can’t explain it”. This book gives evidence and explanations for this. It’s interesting in itself, but the trouble is it has been a very influential book — since it was published, its examples have been cited and reused so many times in so many places that what must once have been groundbreaking now seems overly familiar. I had similar thoughts the last time I saw a performance of Hamlet: the dialogue just seemed to be one cliche after another. Of course, they weren’t cliches when Shakespeare wrote the play!

Even so, the sections towards the end about microexpressions were very interesting and new, at least to me. They give some insight into where the “bad feelings” about people might come from, and maybe some pointers into how you could train yourself to read people and situations better. So even now this is still a worthwhile read from a very influential writer.

This story is more fun than you would think, given that it is about a teenage boy coming to terms with his father’s death. Astronomy and mythology are two of Tuttle’s boyish hobbies; they run like threads through the stories he tells his younger brother and the conversations he has with his friend, and also play a big part in the novel’s resolution. His father, a famous mountaineer, disappeared in controversial circumstances which made his loss even harder for his family to deal with. The repercussions continue even a year later, when the novel is set.

This story is more fun than you would think, given that it is about a teenage boy coming to terms with his father’s death. Astronomy and mythology are two of Tuttle’s boyish hobbies; they run like threads through the stories he tells his younger brother and the conversations he has with his friend, and also play a big part in the novel’s resolution. His father, a famous mountaineer, disappeared in controversial circumstances which made his loss even harder for his family to deal with. The repercussions continue even a year later, when the novel is set. It’s good to finally read this famous book, starring the famous Captain Nemo and his famous ship the Nautilus, and discover that its fame is well-deserved: it’s a page-turning adventure story with drama, intrigue and nifty gadgets.

It’s good to finally read this famous book, starring the famous Captain Nemo and his famous ship the Nautilus, and discover that its fame is well-deserved: it’s a page-turning adventure story with drama, intrigue and nifty gadgets. Jim Flynn’s first

Jim Flynn’s first  This is fun to read and it may change your life. The subtitle describes it best: chaos (particularly perhaps the chaos of the modern world) is what Peterson dreads, and he offers prescriptions, strategies and even commandments for how to preserve an ordered and civilised life from the relentlessly pounding waves of entropy. And all presented using language that virtually demands to be read out loud.

This is fun to read and it may change your life. The subtitle describes it best: chaos (particularly perhaps the chaos of the modern world) is what Peterson dreads, and he offers prescriptions, strategies and even commandments for how to preserve an ordered and civilised life from the relentlessly pounding waves of entropy. And all presented using language that virtually demands to be read out loud. Squalor and alcoholism feature prominently in these short stories based on Berlin’s life. Many of the stories concern marginalised people: they suffer so much injustice but still manage to keep going. Even so, I wouldn’t describe the stories as uplifting.

Squalor and alcoholism feature prominently in these short stories based on Berlin’s life. Many of the stories concern marginalised people: they suffer so much injustice but still manage to keep going. Even so, I wouldn’t describe the stories as uplifting. This is deservedly one of the classic New Zealand novels. When I returned it to the library, the librarian eagerly asked me how it was. I said it was really good — a novel version of Frame’s short stories. The shifting viewpoints give a broad understanding of the characters and events, and the impressionistic first-person narrative really made me feel what it must be like for the main character, living a life very different to mine. Bad things happen to her, but there are also many marvellous moments of beauty:

This is deservedly one of the classic New Zealand novels. When I returned it to the library, the librarian eagerly asked me how it was. I said it was really good — a novel version of Frame’s short stories. The shifting viewpoints give a broad understanding of the characters and events, and the impressionistic first-person narrative really made me feel what it must be like for the main character, living a life very different to mine. Bad things happen to her, but there are also many marvellous moments of beauty: Jim Flynn put this book in his

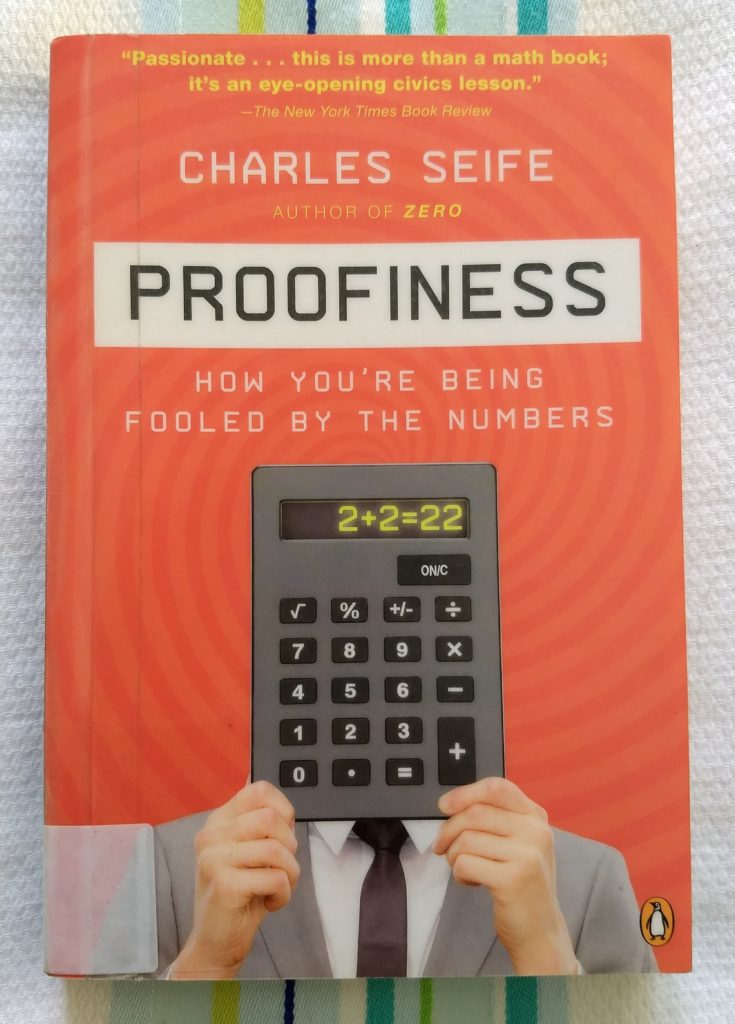

Jim Flynn put this book in his  This is a great survey of all the ways to lie with statistics, and how to avoid being fooled by them. So many of the things we read and hear are based on numerical data, and often it’s hard to argue with them — “the numbers don’t lie”, they say. And it’s true: numbers don’t lie. But people lie, sometimes using words and sometimes using numbers.

This is a great survey of all the ways to lie with statistics, and how to avoid being fooled by them. So many of the things we read and hear are based on numerical data, and often it’s hard to argue with them — “the numbers don’t lie”, they say. And it’s true: numbers don’t lie. But people lie, sometimes using words and sometimes using numbers. The whole idea of mathematics is to make things easier. It allows us to understand the world is ways that would be impossible without it. So it’s a great shame that many people see it as shrouded in mystery. Eugenia Cheng tries to overcome this problem in this book about mathematics and cooking (and in some cases, the mathematics of cooking).

The whole idea of mathematics is to make things easier. It allows us to understand the world is ways that would be impossible without it. So it’s a great shame that many people see it as shrouded in mystery. Eugenia Cheng tries to overcome this problem in this book about mathematics and cooking (and in some cases, the mathematics of cooking).