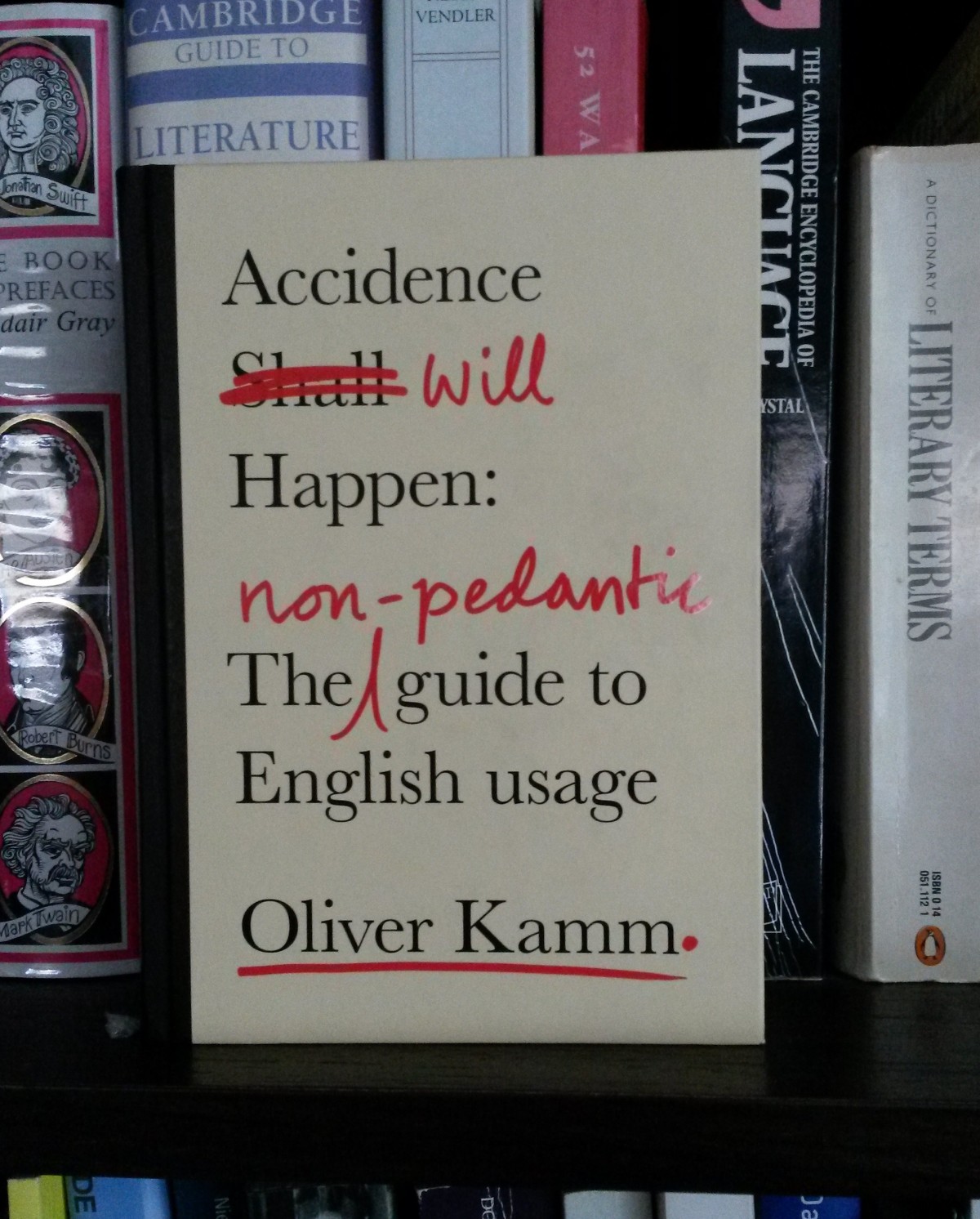

In this book, Oliver Kamm attempts to explode a few myths about English usage, and set out sensible guidelines for literate writing. He gives interesting historical background notes and examples for many of his points, so the book is useful and well worth reading. But even though he chides “sticklers” for their insistence on idiosyncratic rules, his own rules and suggestions are themselves quirky and inconsistent. This makes the book a bit frustrating to read. It’s fun if you enjoy arguing with books though.

In this book, Oliver Kamm attempts to explode a few myths about English usage, and set out sensible guidelines for literate writing. He gives interesting historical background notes and examples for many of his points, so the book is useful and well worth reading. But even though he chides “sticklers” for their insistence on idiosyncratic rules, his own rules and suggestions are themselves quirky and inconsistent. This makes the book a bit frustrating to read. It’s fun if you enjoy arguing with books though.

Kamm is generally very liberal in his views of language: he thinks that language should be allowed to change through usage, and that arbitrary and obsolete rules shouldn’t impede this. He’s right, of course. But he goes both too far and not far enough: he want to throw out some rules that are useful and make the language more usable; yet he wants to keep some obscure rules that make no sense despite his attempts to justify them. I found myself shaking my head and tsking so much that I was moved to pick up a pen and note my disagreement (and, in some cases, my agreement). Here are some examples.

Fraught. Kamm things that situations can only be fraught with something. “The situation was fraught with tension” is OK, but not “the situation was fraught”. I think the second construction is widely understood to imply “… with tension”, so there’s nothing unclear about this common usage.

Effete. Kamm thinks it’s all right for this word to have two unrelated meanings. It is not! Both meanings are pejorative, so in most contexts it will be unclear which meaning is intended. Kamm is too focussed on usage. Sometimes usage leads to ambiguity; this is bad!

Fewer/Less. I agree with Kamm here that the distinction between these two words is useless. “Less” is supposed to be used for continuous quantities and “fewer” for discrete ones, so you’d say “less than three days” if talking about duration (since time is continuous) but “fewer than three days” if you were talking about days of the week (which are discrete). This distinction is much trickier than most people (even pedants) realise. And it’s a worthless distinction: Kamm points out that “more” serves equally well as the opposite to both these words. “Less” should be allowed to cover all cases, and “fewer” becomes unnecessary. And we’ll all be able to stand in the “10 items or less” line with our heads held high.

Double negative. Here, Kamm has helped me to come to terms with the double negative. It’s logical if you realise that each negative applies independently to whatever is being negated. The two negatives don’t apply to each other and cancel out.

Enormity. Yes, senses of words change through time. But we need to at least remember old senses (like the moral sense of “enormity”) so we can read old texts.

Apostrophe. Kamm wants to disagree with the sticklers, but can’t. The rules for apostrophe usage are logical and consistent (except for possessive “its”, and that ain’t going away).

Fulsome. Kamm wants to allow the non-pejorative usage and puts the “onus on the writer” to ensure that the sense is clear. In other words, he admits that the word is not clear in itself. This is the sticklers’ (legitimate) objection.

-gate. I’m not sure why Kamm dislikes this. “Examplegate” is a useful shorthand for “the example controversy”.

Hanged/Hung. The distinction is “not grammar but an accident of history”. But so is everything! This is similar to “its” vs “it’s”. Both distinctions are (as he says) unnecessary and not logical, so why does he approve of the its/it’s distinction but not hanged/hung?

Infer. If you use this to mean “imply” then the reader may stumble. Why not just be unambiguous and use “imply”? Kamm longwindedly uses examples from famous writers to illustrate usage. But this doesn’t make it all right!

Literally. Many words change their meanings over time, and though some sticklers don’t like it, I think it’s perfectly natural and normal. But there is one exception. That exception is “literally”. This word is unique in the language. It is the word that makes it OK to use other words figuratively. Because of that, “literally” is the only word that must always be used literally. There are two reasons that “literally” must never be used figuratively:

– there needs to be a way of cancelling a figurative meaning, and “literally” is the only way

– if “literally” doesn’t mean that, then it has literally no meaning.

Literal “literally” is essential: you can use any word figuratively, except the one word that means you’re not being figurative. In software development, this is called an “escape” — it’s an indication that what follows is to be interpreted in a specific way rather then the normal way. Without the escape provided by “literally”, it becomes hard to use phrases in their literal sense without being misinterpreted.

Figurative “literally” is useless: for example, my friend just told me she is actually an international spy. If I say, “she literally pulled the rug out from under me”, the “literally” adds absolutely nothing to the sentence except ambiguity (was I really standing on a rug? Why did she pull it?).

May/Might. Kamm insists on a very subtle and obscure distinction here. Why here and not elsewhere?

Oblivious. Again, Kamm draws a subtle distinction between “oblivious of” and “oblivious to”. This is pretty much guaranteed to confuse a lot of people, even among the tiny minority who might realise there is such a distinction.

Question mark. “It isn’t necessary to put a point after a question mark.” This seems to be a useless piece of advice, on a par with the old English saying, “it is folly to bolt a door with a boiled carrot.” In all my years I have never seen anybody put a point after a question mark. Perhaps I have just led a very sheltered life: I have also never seen anybody bolt a door with a boiled carrot.

Shall/Will. Here he says, “it would be invidious to list many examples.” If he took his own advice then the book would be shorter and more readable.

Split Infinitives. Like every other similar book I have read, this book reassures us that there’s nothing wrong with splitting infinitives. This is completely uncontroversial: nobody has said otherwise for at least 50 years.

Supersede. He says that we should not be too harsh on people who misspell it “supercede”, because that used to be the conventional spelling. That was 500 years ago! Times have moved on. (But still, “supersede” does seem like an anomaly.)

There are many more contentious statements in the book. In many cases I agree with him, and he does make some good points. He also scores with me by being a fan of P. G. Wodehouse. Really, anybody interested in expressive use of English must appreciate the Master.

Speaking of contentious points, Kamm has no time at all for the Plain English Campaign. He dismisses them as “an aggressively ignorant pressure group”. It’s bracing to see them pilloried like this — their heart may be in the right place, but as Kamm points out, they have made some silly pronouncements.

Kamm talks a lot about Standard English but never defines what he means by that. I don’t think there’s any official definition, but he writes as if there is, often flatly stating that such-and-such a construction “is Standard English” without citing any reference. Also he capitalises the phrase, making it look more official. Or perhaps he’s a fan of A. A. Milne as well as P. G. Wodehouse.

And even worse than not defining his terms, he also fails to properly cite his references: Accidence Will Happen has no bibliography! This book, which is all about words and language usage, both present and historical, and which cites a huge variety of reference and literary works, has no bibliography! I can’t seem to write that without using exclamation marks! It is inexcusable!

So Accidence Will Happen is fun to read. I recommend the hardback, because it makes a satisfying thump when you hurl it across the room in exasperation. When you’ve had enough, you should turn instead to your copy of Steven Pinker’s excellent The Sense Of Style, which offers a far more reasoned, in-depth exploration of the same area.